Web Scraping in Python with BeautifulSoup

What is Web Scraping?

Web scraping is defined as “extracting data from websites or internet” and it is just that — using code to automatically read websites, search something up, or view page sources in order to save some sort of information from them.

This is used everwhere, from Google bots indexing websites, to gathering data on sports statistics, to saving stock prices to an Excel spreadsheet — the options are truly limitless. If there’s a site, page, or search term you’re interested in and want to have updates about, then this article is for you — we’ll be taking a look at how to use the requests and BeautifulSoup libraries to gather data from websites with Python, and you can easily transfer the skills you’ll learn into scraping whichever website interests you effortlessly.

What Tools will we Use?

Python is the go-to language for scraping the internet for data, and the requests and BeautifulSoup libraries are the go-to Python packages for the job. With requests, you can easily scrape any website, and read it’s data in a number of ways, from HTML to JSON. Since most websites are built with HTML and we’ll be extracting all the HTML from the page, we’ll then use the BeautifulSoup package from bs4 in order to parse that HTML and find the data that we are looking for within it.

Requirements

In order to be able to follow along, you’re going to need to have Python, requests, and BeautifulSoup installed.

-

Python: you can download the latest version of Python from the official website, although it’s very likely that you already have it installed.

-

requests: if you have a Python version >= 3.4, you havepipinstalled. You can then usepipin the command line by typingpython3 -m pip install requestsin any directory. -

BeautifulSoup: this comes packaged underbs4, but you can easily just install it withpython3 -m pip install beautifulsoup4.

Programming

I believe that the best way to learn programming is by doing and by building a project, so I strongly encourage you to follow along with me in your favourite text editor (I recommend Visual Studio Code) as we learn how to use these two libraries through example.

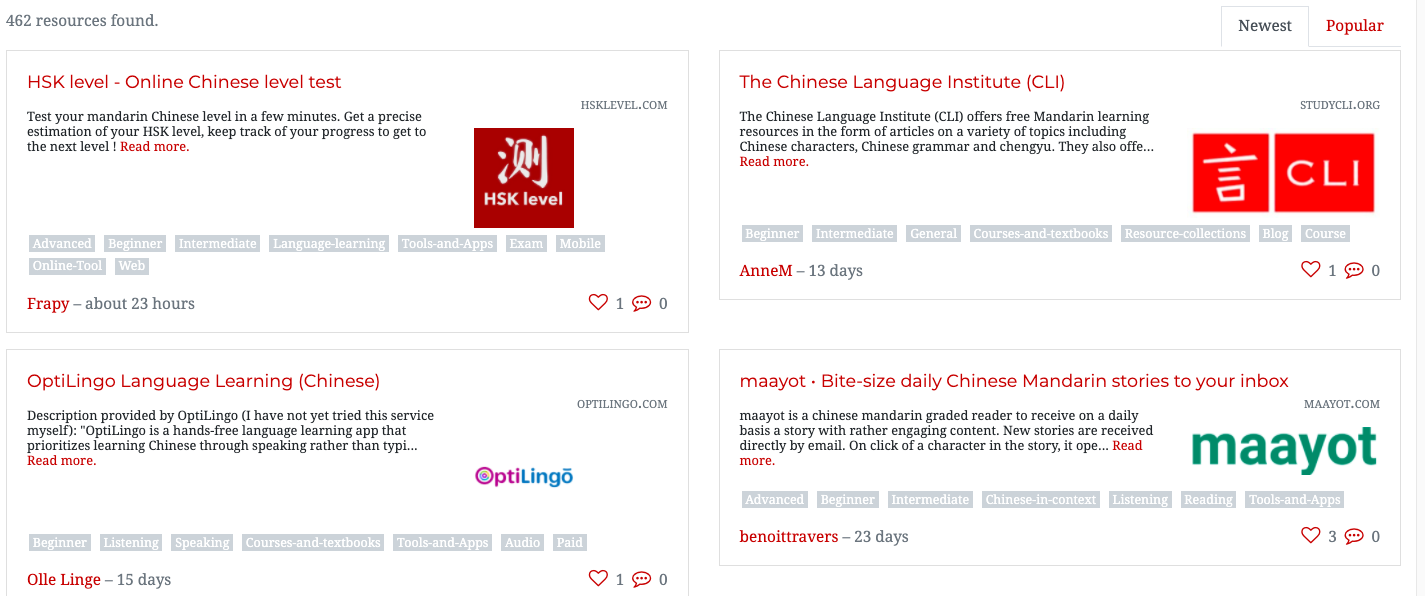

Since I’m learning Mandarin, I thought that it would be apt to build a scraper that generates a list of links to Mandarin resources. Luckily, I did some research beforehand and found out that there is a website online that stores cards-esque lists of Mandarin resources. However, these are spread across nearly a dozen pages, in a card form, and many of the links are broken. The website that we will be scraping these links from is a well-known Mandarin learning website, and you can view the resource list here: https://challenges.hackingchinese.com/resources.

So, in this project, we’ll be scraping the working links from that list and saving them to a file on our computer, so that we will be able to go through them later at our leisure without having to click through every card on the site. The entire program will only be ~40 lines of code, and we’ll be working on the project in three individual steps.

Analyzing the Site

Before we begin with the actual programming, we need to see where the data is being stored on the website. This can be done by “Inspecting” the page. You can inspect a page by right-clicking anywhere within the page and then selecting “Inspect”. If you select that, it will bring up the source code for the page at the bottom of your screen, a bunch of intimidating-looking HTML. Don’t worry — the BeautifulSoup library will make this easy for us.

We’re going to “Inspect” the first result on the website at https://challenges.hackingchinese.com/resources, namely HSK level — Online Chinese level test. To do so, we need to put our mouse right above whatever it is we want to scrape — which is the title, as it is a link as well — and then click “Inspect”, which will open up the source code and move us to exactly where we want to be — at the link.

If you do so, you should see something like the below:

<h4 class="card-title" style="font-size: 1.1rem">

<a href="http://www.hsklevel.com">HSK level — Online Chinese level test</a>

</h4>

Great news! It looks like each link is inside of a h4 header. Whenever we scrape a website for data, we need to look at the unique “identifier” for that data. In this case, it is the h4 header, as there aren’t any others on the site that aren’t related to the links. Another option could be searching based on font-size or the class of card-title, but we’ll go for the h4 header as that is the simplest.

Scraping the Resource Links

Now that we’ve figured out how the website source looks, we need to get to actually scraping the content. We’ll be saving each links to a file on our device named links.txt, and need just a few dozen lines to get the job done.

Let’s get started.

- Importing Libraries

We need the aforementioned libraries to get the program running. Create a new file namedscrape_links.pyand write the following:

import requests, time from bs4 import BeautifulSoup - Scraping the Site

Since the website has its resources divided across several pages, it makes sense to scrape it within a function so that we can repeat it. Let’s name this functionextract_resources, and it will have a parameter defining its page number.

def extract_resources(page: int -> None): # use an f-string to access the correct page page = requests.get(f'https://challenges.hackingchinese.com/resources/stories?page={page}) soup = BeautifulSoup(page.content, 'html.parser')We are using the

soupvariable to hold aBeautifulSoupobject of the website. We’re converting it to HTML withhtml.parserand the data that we are converting is the content of thepagevariable.links = soup.find_all('h4')We’ll be using

BeautifulSoupto find all of the HTML that are headers, and will save them in a list namedlinkswith their children html (in this case, the link). - Gathering our Data

for i in range(len(links)): try: if links[i]['class'] == ['card-title']: true_links.append(links[i]) except: passOn the first line, we are iterating through every h4 header in

links. We check to see if its class iscard-title, like we saw in Analyzing the Site, in order to make sure that we avoid any h4 headers that aren’t cards — just in case. If it is a card-related h4 with a link, then we are going to append it to the previously empty listtrue_linkswith all correct h4s.

Finally, we’ll wrap this in atry: except:loop in case the h4 has no case, to prevent the program from crashing asBeautifulSoupcan’t handle the request. - Saving the Links

# open file with w+ (generate it if it does not exist) file = open("links.txt", "w+") for i in range(len(true_links)): file.write(str(list(true_links[i].children)[0]['href']) + '\n') file.close()Instead of printing out the list, let’s save it so that we don’t need to run the Python file multiple times and have it in an easier-to-view format.

First, we open the file, and we are opening it withw+so that if it does not exist, we can generate a blank file with its name.

Second, we iterate through the list oftrue_links. For each element, we write to the file with its link usingfile.write(). When we were first analyzing the site, we saw that the link is a child element of the h4 HTML header. So, we useBeautifulSoupto access the first child oftrue_links[i], which we need to wrap in a list as it is otherwise a Python object.

At this point, we havelist(true_links[i].children)[0]. However, what we are looking for is the actual link of the child. Instead of<a href="abc.com">Text</a>we want just the link, which we can access with['href']. Once we have this, we need to wrap the whole thing in a string so that it is outputted as a string and then add ‘\n’ in order to ensure that each link is on a new line when wefile.write()it.

Lastly, we performfile.close()in order to close the file we opened.

If you run the program and give it a few minutes, you should find that you now have a file namedlinks.txtwith hundreds of links that we scraped with Python! Congratulation! Without Python, it would have taken much longer to manually grab each URL.

Before we finish off, we’re going to see another way in which we can use therequestslibrary by checking the status of each link.

Bonus: Removing Dead Links

The website that we are scraping isn’t kept in great condition, and a few of the links are outdated or dead entirely. So, in this optional step, we’ll see another aspect of scraping which returns the status code of each website, and discards them if it is a 404 — meaning not found.

We are going to need to slightly modify the code used in Step 4 above. Instead of simply iterating through the links and writing them to the file, we are going to first ensure that they aren’t broken.

file = open("links.txt", "w+")

for i in range(len(true_links)):

try:

# ensure it is a working link

response = requests.get(str(list(true_links[i].children)[0]['href']), timeout = 5, allow_redirects = True, stream = True)

if response != 404:

file.write(str(list(true_links[i].children)[0]['href']) + '\n')

except: # Connection Refused

pass

file.close()

We’ve made a few changes — let’s go over them.

- We created a

responsevariable which checks the status code of the link — essentially seeing if it is still there. This can be done with the usefulrequests.get()method. We are getting the same link that we are trying to append, namely the website URL, and giving it 5 seconds to respond, the chance to redirect, and allowing it to send us files (which we won’t download), withstream = True. - We checked what the response was, by seeing if it was a 404 or not. If it wasn’t, then we wrote the link, but if it was, then we did nothing and did not write the link to the file. This was done through the conditional

if response != 404. - Lastly, we wrapped the whole thing in a try — except loop. That’s because if the page was slow to load, couldn’t be accessed, or the connection was refused, then ordinarily the program would crash in an Exception. However, since we wrapped it in this loop then nothing will happen in the case of an Exception and it will only be passed over.

And that’s it! If you run the code (and leave it running too, because for requests to check hundreds of links it can take a good half-hour) when it finishes you’ll have a beautiful set of a few hundred working resource links!

Full Code

# grab the list of all the resources at https://challenges.hackingchinese.com/resources

import requests, time

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

# links that hold the correct content, not headers and other HTML

true_links = []

def extract_resources(page: int) -> None:

page = requests.get(f'https://challenges.hackingchinese.com/resources/stories?page={page}')

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.content, 'html.parser')

# links are stored within a unique <h4> header on each card

links = soup.find_all('h4')

for i in range(len(links)):

try:

if links[i]['class'] == ['card-title']:

true_links.append(links[i])

except:

pass

for i in range(1, 10):

extract_resources(i) # 9 different pages with info

file = open("links.txt", "w+")

for i in range(len(true_links)):

try:

# ensure it is a working link

response = requests.get(str(list(true_links[i].children)[0]['href']), timeout = 5, allow_redirects = True, stream = True)

if response != 404:

file.write(str(list(true_links[i].children)[0]['href']) + '\n')

except: # Connection Refused

pass

file.close()

Conclusion

In this post, we’ve learned how to:

- View a page source

- Scrape a website for specific data

- Write to files with Python

- Check for dead links

Although we only touched the surface of the sort of web scraping that can be done in Python with the proper libraries, I hope that even this quick intro has taught you how to leverage the power of programming to automatically scrape websites. I highly encourage you to check out the official documentation for both requests and BeautifulSoup if you want to take a deeper dive into the world of data scraping, and see if there is any data that you can gather from the web and use in your own projects.

Let me know in the comments what you’re scraping or if you need any more help!

Happy Coding!

Leave a comment